Library

|

The Vanished Rajesh Ramachandran. Outlook India, Aug 15, 2005

From 1984 to 1994, the Punjab Police was at its brutal best. A decade later, NHRC is still to administer justice.

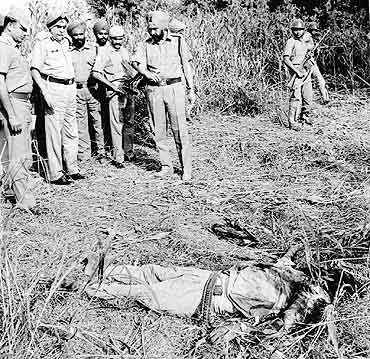

September 6 is an unpleasant milestone in the story of death by disappearance in Punjab. On that day, 10 years ago, Akali Dal leader Jaswant Singh Khalra, who told the world the shocking story of young men in Punjab disappearing and being illegally cremated, was himself made to disappear. The trial into Khalra's alleged abduction and murder by the Punjab Police, then the fiefdom of supercop K. P. S. Gill, is still going on in a Patiala court. And the trials and tribulations of the families of those who disappeared in the murderous days of militancy seem to be endless, their search for justice almost a lost cause. The allegations of police brutality in Punjab between 1984 and 1994 is more chilling than any horror film. Human rights activists allege the police picked up thousands of young men some confirmed militants, some sympathisers and many innocents from across the state, killed them in cold blood and despatched them as unidentified corpses to various crematoriums across the state. There were more weighed down in canals and rivers. No one knows how many disappeared in this manner. However, 2,097 illegal cremations, pertaining to just three crematoriums in Amritsar district Durgyana Mandir, Municipal Committee and Tarn Taran have been confirmed by a CBI investigation. The NHRC, inquiring into the entire case for the last eight years now, has tended to concentrate on the illegality of the cremations rather than the allegations of rights violation and cold-blooded murders. It has also been slow in awarding compensation to families of those cremated. In fact, last November, the NHRC awarded a compensation of Rs 2.5 lakh each to only 109 families. As many as 1,886 families have got no relief. Of the 109 cases where compensation has been paid, the Punjab Police has admitted that it had custody of 99 persons before they were killed. The police claims that all of them were killed in encounters and they could not safeguard the lives of terrorists. In almost all the cases, the police's story is the same: the man in custody was being taken, usually in the dead of night, to recover arms when other militants attacked the police party and killed the terrorist in custody. But not a single policeman was recorded as killed in these encounters where automatic weapons were often used. But the NHRC did not question why only those in custody were killed during such encounters. This despite the NHRC noting in its findings that "the state of Punjab is, therefore, accountable and vicariously responsible for the infringement of the indefeasible right to life of those 109 deceased persons as it failed to safe-guard their lives and persons against the risk of avoidable harm".

The NHRC refused to respond to Outlook's questionnaire or comment on the various contentious issues since it could prejudice the process of inquiry. Human rights activists allege the NHRC has been softer on the police than the victims. They say the police should have been put through more stringent probing, especially their claim of having had only 99 victims in custody. One of the key petitioners, the Committee for Information and Initiative on Punjab (CIIP), says on the basis of its documentation that the police had custody of 146 people before they were killed and illegally cremated. Then the NHRC arrived at the figure of 109 through its own "independent analysis". According to the petitioners, the police have admitted custody in certain cases because the families got these arrests documented by writing petitions or sending telegrams to public functionaries. The Punjab Police has always claimed a degree of immunity on the grounds that this was a 'war against terror' and its officers should not be held guilty for custodial deaths and cremations. In a recent hearing, the police counsel even argued that the Indian state (and its security forces) had behaved in a far more humane fashion in Punjab than the US forces in Iraq. Altaf Ahmed, the counsel who drew this analogy, was not available for comment. It is another issue that even in war, custodial deaths are illegal under the Geneva Conventions. The NHRC, on its part, has virtually limited the scope of its inquiry to illegal cremations in the three crematoriums of Amritsar. The CIIP had documented hundreds of similar illegal cremations in other districts of Punjab, like Faridkot, Kapurthala, Ludhiana and Mansa. But the Commission has refused to look into these. Also, the NHRC is yet to question the snail's pace at which the CBI is prosecuting the Punjab Police officers. Only about 30 cases are being tried in Patiala and even Khalra's case has not reached its conclusion. This despite a special police officer, Kuldip Singh, testifying recently in the Patiala court that he had seen former Punjab Police chief K.P.S. Gill going into the room where Khalra was kept a week before he was killed. According to rights activists, too many high-profile officers are involved in the case, which explains why the case is making slow progress. The Khalra case had its beginnings in a press conference held by the Akali leader in January 1995. In it, he revealed that thousands of extra-judicial killings had happened in Punjab since 1984 and that these bodies were illegally cremated all over the state. He had the records of three crematoriums in Amritsar, which he made public. But the Punjab and Haryana High Court didn't entertain his petition. Soon after, he was abducted. A telegram on Khalra's abduction, sent by the then Shiromani Gurudwara Prabhandak Committee president Gurcharan Singh Tohra, was treated as a petition by the Supreme Court, which asked the CBI to investigate the case as also the illegal cremations. The CBI came up with the figure of 2,097 illegal cremations in the three crematoriums. Among these, the CBI identified 582 bodies, provisionally identified another 278 and listed 1,237 as unidentified. The Supreme Court referred the matter to the NHRC in December 1996, giving the latter all authority to deal with the issue. Even when the Centre challenged the NHRC's authority, the Supreme Court held in September 1998 that, "in deciding the matters referred by this court, the NHRC is given a free hand and is not circumscribed by any conditions". That is, the CBI would look into the culpability of the police officers in killing/cremating people and the NHRC would probe the remaining issues, particularly those related to human rights violations. Of course, the Supreme Court expected a "quick conclusion" from the NHRC. That was seven years ago. After the CBI identified 582 bodies, the Punjab Police admitted they knew the identity of 376 bodies. According to its affidavit, 321 were identified on the spot. This means that 65 per cent of the bodies were identified before cremation, yet the police did not hand over the bodies to the families. The CIIP's Ashok Agrwaal claims that his organisation could place an additional 175 corpses, taking the count of fully identified bodies to 757. He says: "There was no justification for the cremation of identified bodies terming them unidentified/unclaimed, unless it was a matter of policy at the highest level of the Punjab Police. If cremation was a matter of policy, then it indicates that the murder of these persons could have been a matter of policy too". Despite a decade of delay and apathy, the families of the 'missing and cremated' are waiting for justice. As for the CIIP, it sees its 10-year-long fight as not one just about Punjab. Says Agrwaal: "The issue is about the impunity with which the institutions of the state trampled on the most basic of fundamental rights "the right to life". |